This week, I hopped on a train to Berlin to see some of the pieces that I have been studying. I think it’s always helpful to see pieces in person (if possible), and I always find museums inspiring–you never know what you’re going to discover that could help your research.

One of my pet interests is theory and authenticity. In other words, I enjoy researching and thinking about ancient and modern forgery. I wasn’t expecting to spend time thinking about this on my trip to Berlin, but, as suggested above, you never know what you’ll find in a museum that will inspire you.

The first piece that caught my eye is the statue of Antinous. I found this piece particularly attrative because of the detail in the marble carving. Look at those teeth!

Aside from the amazing detail, this piece also had quite an interesting story. It was originally a headless marble statue that was completed in the 18th century by adding a (bodyless) marble head depicting Antinous. Both the head and the body are ancient fragments of statues, but the composition of the two is more modern.

A similar example is the “Julio-Claudian Prince.” The head is probably datable to around 4 CE, and likely does depict a Julio-Claudian prince, whereas the body is that of a general from the Flavian period.

One of my favorite questions to ask with cases like these is: since the whole of the piece doesn’t date to the same period, does that make it “real” or “fake?” Could it be considered a reused, recycled, or repurposed object? Is the final product a misleading deception or a fragmented piece improved upon in order to aid its interpretation by viewers?

Without dwelling too much on this topic (about which I could hold forth for some time), I find that pieces like this are generally “authentic.”For, these pieces, despite having been altered in different periods, generally still have great value for studying the past (whether ancient or more modern).

So, the next question may be: if it has been changed in different periods, what is the date of the piece? In what context can we place this piece: the earliest, middle, or latest date that the monument was altered?

This line of thinking always reminds me of the Getty Kouros (more here), a controversial piece. The Kouros has been much scrutinized–in part because of its fraudelent collecting history and in part because of the inability for anyone to prove its authenticity with certainty. In order to reconcile these issues, the Kouros is currently dated to “530 BCE or modern forgery” according to the Getty webpage. This is to say, if you don’t know which date it is, why not both!I find this tactic especially interesting because, in some ways, it allows the viewer to make a judgement.

For the two pieces from Berlin, the text labels are clearer. They list all of the possible dates: the date of the head, the date of the body, and describes in the date of the assilimation of the pieces. This allows the visitor to know the whole story, even if it means there isn’t one definive date for the piece.

What is also interesting to me is that in one case the title of the piece describes the history/composition with the title “Collosal Statue with Cornocopia, Snake, and Portrait of Antinous”), whereas the other just describes the head “Julio-Claudian Prince,” leaving out the identification of the body as a Flavian soldier from the title.

But why add these pieces together in the first place if they come from different periods and depict different scenes? For these pieces, someone in the 17-19th centuries decided it would be better for the piece to be whole than for the piece to be accurate/authentic (different perception of art). Or perhaps the person genuinely thought the pieces matched (bad archaeology?). Or, even, the person did it in order to raise the value of the piece on the art market–to make more money (economic reasons). Pieces like these are interesting glimpses into the past. From these examples, we can begin to understand how people in the past valued and understood ancient art.

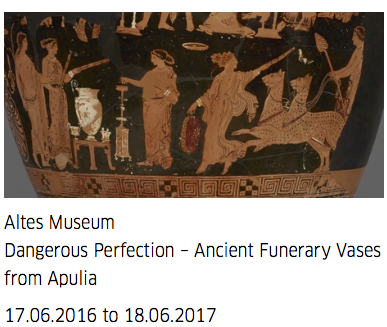

This very idea was discussed in the “Dangerous Perfection” exhibition, also currently at the Altes Museum.

This exhibition tells the story of the discovery, forgery, and acquisition of 13 pieces of pottery from Southern Italy. The pieces were sold as fragments to a restorer who pieced them back together along with expertly crafted and painted pieces to fill the gaps. When the pieces were finished, they were so complete and so perfect, “it was often impossible to distinguish ancient parts from the modern additions, leading to what contemporaries termed, ‘A Dangerous Perfection‘” (Introductory text).

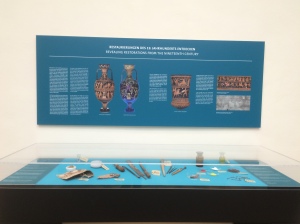

The exhibition discussed the story behind these pieces. The exhibit also focused on the 2008-2014 joint project between the Berlin Museums and the Getty Museum to restore the pieces because of damage caused during WWII. Over the course of the project, the team was able to determine which fragments of the vessels were original and which were the deceptive pieces, using techniques like UV light and X-ray analysis.

Once they were able to do identify which fragments were ancient and which were modern, the conservation experts deconstructed the vases, removed the 19th century pieces, and replaced them with blank pottery pieces. They did this so that visitors would not continue to be decieved by the 19th century interpretation of what the missing scene ought to be. Since the original scene no longer exists, any guesses at what might be in the missing area would be misleading to the viewer.

Because the forged pieces are still a very important part of the story of these objects (and to art history), the pieces were treated and will be kept as part of the museum’s collection.

For me, this is a heartwarming story. A group of objects once seen as original, then seen as fake, and now can be understood having at one point or another been both. I especially appreciate the value given to the process that the forger used to make the convincing pieces, as well as the value placed on his work in terms of art history and object history.

Not only did the exhibit tell a very interesting story about issues close to my heart (what does it mean to be fake, do fake objects have value, what can we learn from forgeries?), but it was also very well done and engaging. Although I give a brief overview here, it is definitely work seeing the objects and the process in person!

These pieces and exhibition were great examples of how we can think about the concepts of authenticity in museums: how real does something have to be to be considered authentic? How altered does something have to be to be considered forged? How can museum address and display objects with complicated pasts?

In summary, if you find yourself in Berlin and you’re interested in contemplating issues of authenticity, display, and object history, check out these pieces at the Altes Museum!

[…] instance, the statues that I discussed in the previous post, are authentically ancient objects combined in a non-original context to create a new piece of art. […]

LikeLike